Effective delivery of therapeutic molecules like medications, genes, and proteins into cells is made possible by the novel biophysical technique known as magnetoporation, or magnetofection, which uses magnetic fields and nanoparticles to permeabilize cell membranes temporarily. This technique has become a viable substitute for conventional delivery methods because of its great accuracy, decreased cellular damage, and increased efficacy. Magnetoporation is at the forefront of developments in drug delivery, gene editing, and regenerative medicine as the medical field moves increasingly toward non-invasive and targeted therapies.

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) are the carriers used in this technology. When they are subjected to an alternating magnetic field, these nanoparticles produce mechanical forces that temporarily breach cell membranes, enabling big molecules to get past the membrane’s built-in defenses. Magnetoporation is a flexible tool for both research and clinical applications because it overcomes important drawbacks of traditional techniques like electroporation (which uses electrical pulses) and viral vectors (which pose immunogenic risks).

This article examines magnetoporation’s biophysical principles, mechanisms, benefits, drawbacks, medical applications (especially in drug delivery and gene therapy), safety issues, technological developments, and potential future uses.

Fundamentals of Magnetoporation

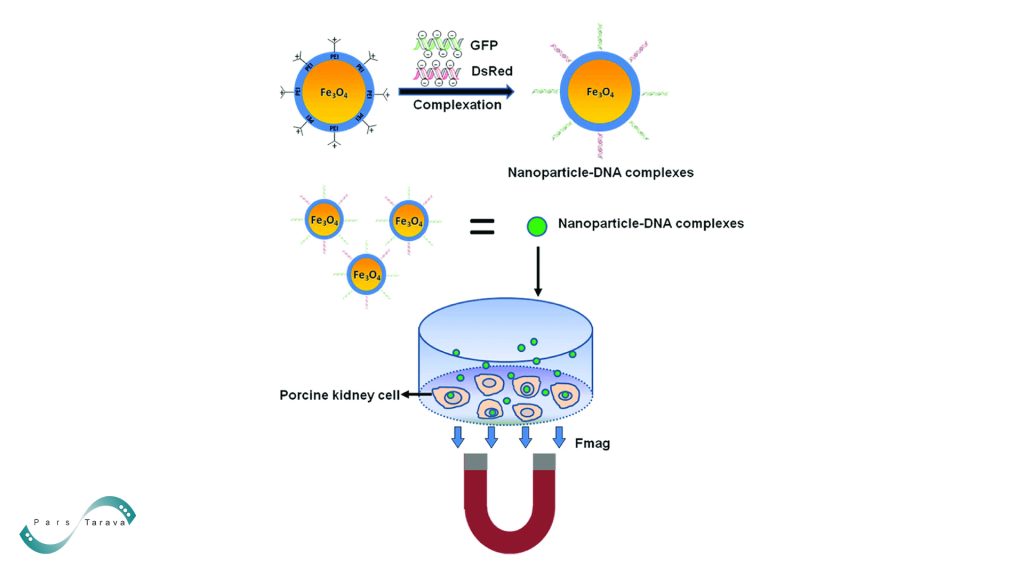

External magnetic fields are used in magnetoporation to direct magnetic carrier nanoparticles to their target locations. Usually made of iron oxide (FeO₄), these nanoparticles are chosen for their superparamagnetic characteristics, biocompatibility, and simplicity of surface modification. They are between 10 and 100 nm in size. They are frequently coated with substances like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or specific ligands like antibodies to improve stability and cell-specific binding.

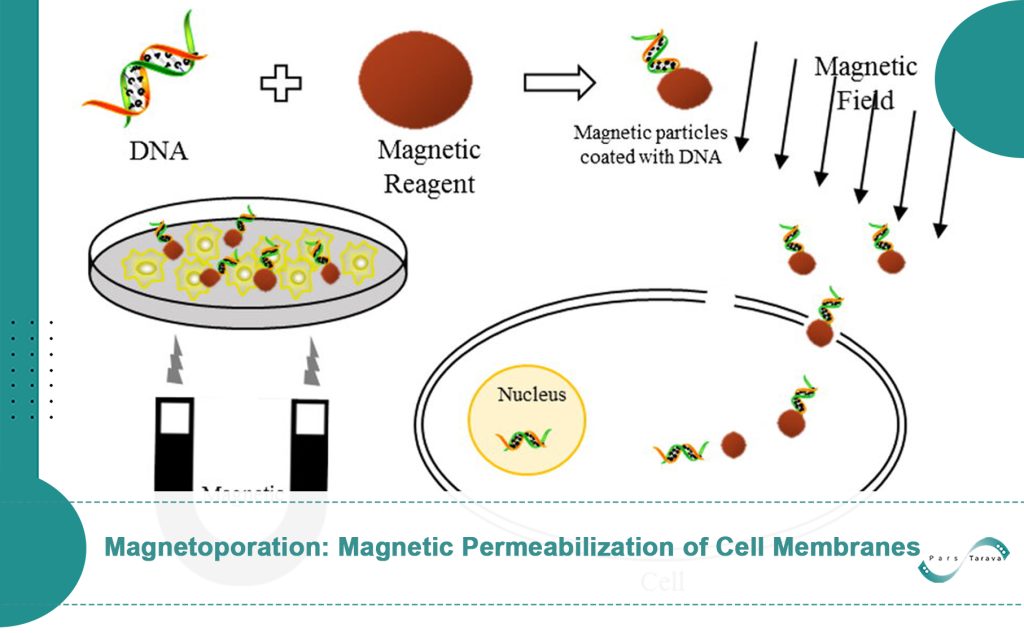

There are two main steps in the process:

Cellular Uptake of Nanoparticles: Magnetic nanoparticles with therapeutic or genetic payloads speed up the internalization of molecules by using magnetic forces to attract target cells.

Application of a Magnetic Field: The nanoparticles experience mechanical stress from an external alternating magnetic field, which causes oscillations that break the lipid bilayer and produce temporary pores.

Because pore formation is reversible, long-term cellular damage is reduced. Efficiency is greatly influenced by factors like nanoparticle size and shape, exposure time (milliseconds to minutes), and magnetic field strength (usually 0.1–10 Tesla). Research shows that applying a magnetic field improves gene transfer efficiency while lowering the dosage of genetic material needed compared to traditional transfection techniques. In biology, endocytosis or protein pump mechanisms allow nanoparticles that have gathered at the cell surface to enter cells.

Action Mechanisms

The physical and biological processes that underlie magnetoporation differ based on the type of carrier and the circumstances of the experiment. Charged molecules, such as nucleic acids, attach to magnetic nanoparticles in magnetofection-based methods, and these complexes are concentrated close to target cells by an external magnetic field. Gene vectors, whether viral or non-viral, are guided toward cells by magnetic forces, allowing for the quick and effective delivery of nucleic acids.

Once they reach the cell surface, metallic particles may produce weak electromagnetic fields or localized mechanical effects to increase membrane permeability. Cationic-coated magnetic nanoparticles can also release cargo after entering intracellular vacuoles (endosomes) through endocytosis.

To enhance membrane permeability in drug delivery applications (like chemotherapy), pulsed magnetic fields are applied to tumors or diseased tissues following drug injection (like bleomycin). For example, a study conducted on tumor-bearing mice showed that post-intratumoral bleomycin injection, magnetic pulses (3.5 Tesla, 8 pulses of 160 μs at 1 Hz) increased drug uptake seven times more than controls. These results demonstrate how magnetic fields may improve drug penetration, though stronger fields or longer exposure times may be necessary to achieve noticeable permeabilization.

Magnetoporation Benefits

Compared to conventional gene or medication delivery techniques, magnetoporation has the following benefits:

- Enhanced Efficiency: Lower genetic material dosages and higher transfection rates.

- Targeted Delivery: Magnetic fields help reduce systemic side effects by enabling localized delivery. Functionalized nanoparticles prevent the dangers of viral vector integration and lessen off-target effects.

- Minimal Cellular Damage: Non-invasive as opposed to invasive electrodes needed for electroporation.

- Scalability: Fit for uses ranging from organ-level therapies to single-cell manipulation.

Obstacles and Restrictions

Strong magnetic fields with high gradients are necessary for effective nanoparticle guidance, which presents difficulties for thick or deeply seated tissues. Injecting local nanoparticles or using specific carrier designs might be required.

Toxicity Issues: Because some polymer coatings (like PEI) can cause cytotoxicity, it’s important to adjust the pH levels and coatings of nanoparticles carefully.

Reproducibility: Standardization is made more difficult by variations in magnetic field parameters and nanoparticle synthesis.

Applications in Medicine

Gene therapy:

Magnetoporation outperforms electroporation in primary cells, achieving up to 80% transfection efficiency. It makes it possible to precisely deliver siRNA, CRISPR-Cas9, or viral or non-viral vectors (like liposomes or adenovirus) into target cells. Studies on animals verify that therapeutic genes, such as tumor suppressors, are successfully expressed.

Targeted Drug Delivery:

Chemotherapeutic agents like doxorubicin are delivered directly to tumors, decreasing systemic toxicity. Studies have shown that cancer cells exhibit improved apoptosis and a 60% increase in drug uptake.

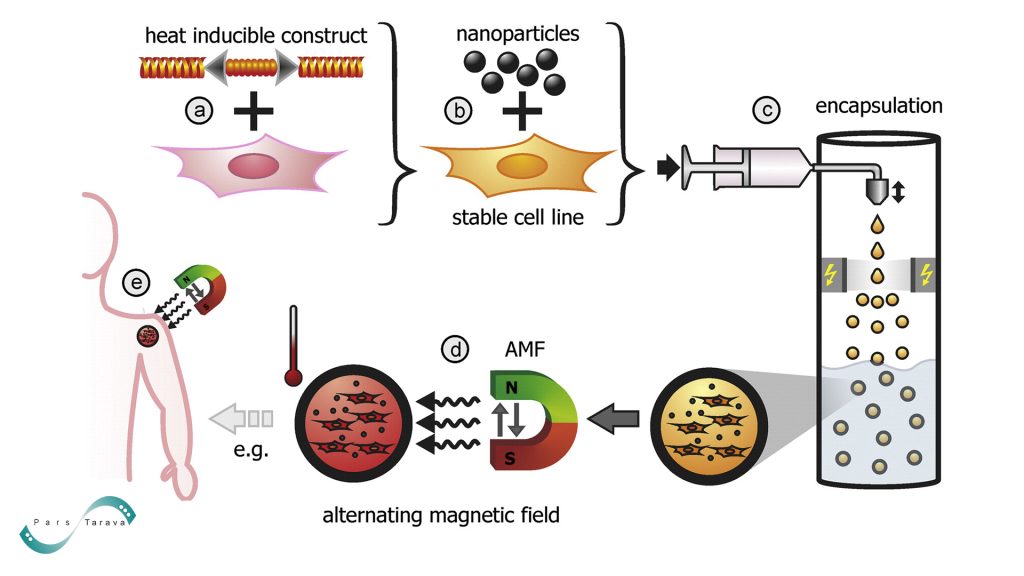

Magnetic Hyperthermia:

In vitro, 70% of glioblastoma cells are eliminated, while healthy tissue is left intact by thermally sensitive MNPs that produce localized heat under alternating magnetic fields.

Regenerative medicine:

MNPs give stem cells mRNA or growth factors. For instance, compared to traditional techniques, chondrogenic differentiation rates were tripled when BMP-2 mRNA was delivered to mesenchymal stem cells.

Safety Factors

Because magnetoporation is non-invasive, there is a lower chance of burns or other physical trauma from the electrodes. Like MRI contrast agents, iron oxide nanoparticles are biocompatible and naturally degrade; however, more research is needed to determine the long-term toxicity of coatings like cationic polymers. Intense magnetic pulses can heat tissue or cause mechanical damage if misused, so field parameters must be precisely calibrated. Although preliminary research indicates few adverse effects, thorough preclinical and clinical testing is necessary.

Developments in Technology

New nanoparticle designs and magnetic field optimization are the main topics of recent innovations:

Smart Nanoparticles: MNPs that respond to temperature or pH allow for controlled payload release, such as medication release in acidic tumor microenvironments.

Biodegradable MNPs: After delivery, magnesium-based nanoparticles break down, removing the possibility of accumulation.

Hybrid Techniques: Neuronal cell transfection efficiency increases by 40% when magnetoporation and electroporation are combined, or “magneto-electroporation.”

Magnetogenetics: Engineered magnetosensitive molecules, such as ferritin, enable gene regulation via magnetic fields, opening up new possibilities for gene therapy.

Future Directions

Clinical validation, advanced magnetic field sources (like superconducting magnets), and biocompatible coatings (like peptides and natural polymers) will be the primary focus of future research. Precision will be further improved by integrating AI-driven optimization models and complementary technologies (such as microplasmas and bioreactors). Magnetoporation can potentially transform genetic therapies and targeted drug delivery as magnetic systems and nanoparticles advance.

In conclusion

By combining magnetic nanoparticles and fields to increase membrane permeability, magnetoporation signifies a paradigm shift in cellular delivery. It offers revolutionary potential for pharmaceutical and genetic treatments by getting around the drawbacks of traditional approaches. Its place in precision medicine will be cemented by ongoing clinical research and materials science developments, opening the door to safer and more efficient treatments.