Irreversible Electroporation (IRE): An Innovative Non‑Thermal Technology for Tumor Ablation

Irreversible electroporation (IRE) is a novel, non‑thermal tumor ablation technique that employs short, high‑voltage electrical pulses to induce permanent nanopores in the cell membrane, ultimately triggering cell death. Unlike thermal ablation methods (e.g., radiofrequency or microwave), which can cause collateral thermal necrosis of surrounding structures, IRE spares the extracellular matrix—including collagen, elastic fibers of vessels, and nerves—enabling the safe treatment of tumors adjacent to critical anatomical structures (such as major blood vessels, bile ducts, and nerves). Furthermore, IRE does not rely on chemotherapy or specialized chemicals; it destroys target cells solely through electric energy. Treatment parameters depend on the applied voltage, pulse duration, number, pulse repetition rate, and the distance between electrodes and the tumor.

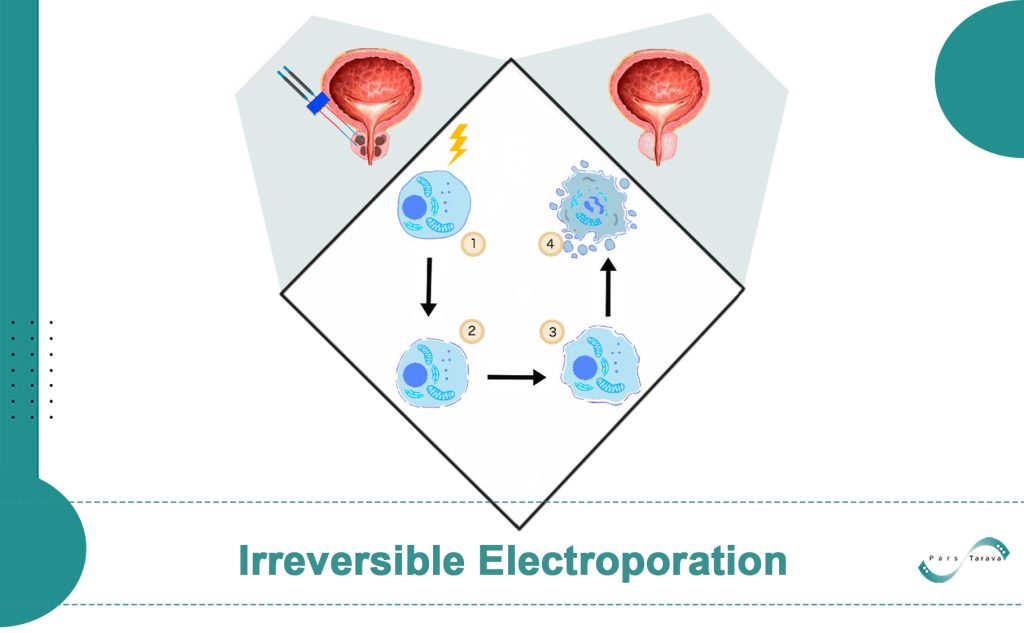

Mechanism of Action

In IRE, high-intensity electric fields are delivered as microsecond‑duration pulses, creating pores in the cell membrane. If the field strength exceeds a critical threshold, cells cannot repair these pores, osmotic balance is lost, and apoptosis ensues. Immune system activation was also observed following IRE. Key parameters influencing efficacy include voltage amplitude, pulse count and repetition rate, electrode spacing, and the electrical conductivity of the target tissue. Optimizing these variables is essential to achieve an effective ablation zone.

Reversible vs. Irreversible Electroporation

Electroporation broadly refers to the formation of transient or permanent pores in cell membranes via electrical pulses. When field strength is below a reparative threshold, the membrane reseals—this is reversible electroporation, commonly used for gene transfer, targeted drug delivery, or electrochemotherapy. If the field exceeds a critical threshold, membranes cannot reseal, leading to cell death; this is irreversible electroporation (IRE). Unlike its reversible counterpart, IRE requires no adjunctive chemicals and is primarily applied to solid tumor ablation.

Clinical Applications

Liver Tumors (HCC and Metastases):

IRE is particularly suited to hepatic tumors located near major vessels (e.g., portal vein, inferior vena cava) or bile ducts, which are unsuitable for thermal ablation. Studies have demonstrated that IRE can achieve precise ablation margins without damaging vascular or biliary structures. Systematic reviews report a post‑IRE complication rate of approximately 16%, predominantly mild, probe‑related events. Among 158 vessels adjacent to treated tumors, only 4.4% exhibited minor vascular changes. IRE effectively treats tumors up to several centimeters in diameter, with most clinical procedures focusing on lesions measuring 2–3 cm.

Pancreatic Tumors:

Advanced pancreatic tumors often involve major vessels, rendering surgical or thermal approaches challenging. The non‑thermal nature of IRE preserves vascular integrity, allowing tumor cell destruction alongside vessels without inducing ischemia. Preliminary studies indicate acceptable safety and efficacy, although current use remains largely investigational or palliative.

Prostate Tumors:

In prostate cancer, IRE’s ability to preserve nerves and organ function is particularly advantageous. While mucosal layers may be affected, the gland’s overall architecture remains intact, reducing risks of sexual and urinary dysfunction. Animal studies, followed by limited clinical trials, have shown good tolerance and effective tumor ablation. In one canine study involving six males, no mortality or serious adverse events were observed; early human trials similarly report promising tumor control with preserved erectile and urinary function.

Other Solid Tumors:

IRE has also been explored in limited series for renal, pulmonary, breast, cerebral, and soft‑tissue tumors. For instance, animal studies in lung models demonstrate feasibility, and in kidney parenchyma, larger ablation zones have been achieved with minimal complications.

Patient Selection and Treatment Workflow

Proper patient selection and pre‑procedure preparation are critical. Multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) typically assess candidates requiring good performance status (e.g., ECOG ≤2) and the absence of widespread metastases. Anatomically, IRE is reserved for locally advanced tumors adjacent to vital structures when alternative treatments are ineffective. Cardiac history must be reviewed, as serious arrhythmias or pacemaker implantation are contraindications. Imaging (CT/MRI) evaluates tumor dimensions and relations, and anesthesia consultation ensures safe general anesthesia with neuromuscular blockade.

Treatment Steps:

- General Anesthesia with Muscle Blockade: Prevents muscle contractions induced by pulses.

- Cardiac Synchronization: Gating devices time pulse delivery between non‑excitatory cardiac phases (between R‑waves), reducing arrhythmia risk. Early cases without gating experienced transient arrhythmias, prompting routine gating.

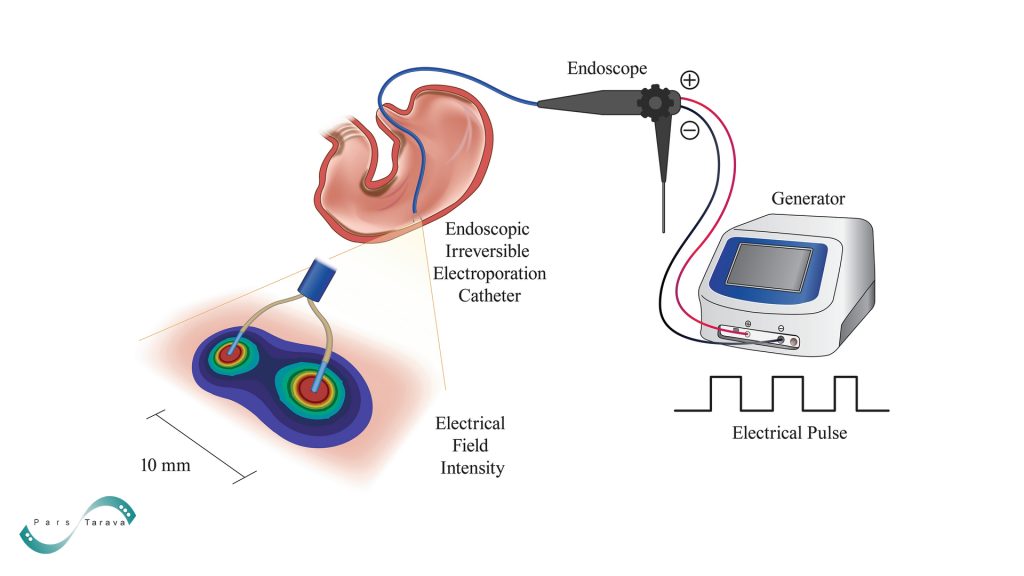

- Image‑Guided Electrode Placement: Two to six monopolar electrodes with sharp tips are positioned around the tumor under ultrasound, CT, or combined guidance to encompass the entire target. Electrode spacing is typically 1.5–2 cm, arranged in triangular or planar arrays matching tumor shape. Parallel alignment (<10° divergence) and co‑planar tips ensure uniform ablation.

- Electrical Pulse Delivery: Initial test pulses (~10 pulses per electrode pair at 20–50 A) assess tissue response. Subsequently, ~70 treatment pulses (70–90 µs each) are applied, incrementally increasing current by 12–15 A per pulse across adjacent electrode pairs to cover the tumor.

- Assessment of Ablation Zone: Intra- or peri‑procedural imaging (CT or ultrasound) evaluates hypo‑echoic or gas‑forming areas indicative of ablation. If necessary, electrodes are repositioned, or additional pulses are delivered.

- Post‑Procedure Care: This focus is on pain management, vital sign monitoring, and the function of the treated organ. Transient elevations of AST, ALT, and bilirubin are common within 24 hours and resolve over weeks. Regular blood work and clinical follow‑up are recommended.

Safety and Complications

IRE’s safety largely stems from the preservation of peritumoral vascular and neural structures. Studies confirm minimal vascular changes post‑IRE of hepatic tumors, with major vessels remaining patent. Biliary structures tolerate the procedure similarly, with occasional transient strictures that resolve spontaneously.

Procedure‑Related Risks:

- Cardiac Arrhythmias: Although gating greatly reduces risk, early reports documented transient arrhythmias; patients with serious rhythm disorders or pacemakers are excluded.

- Muscle Contractions: Even under complete muscle blockade, localized contractions at probe sites may occur, underscoring the need for adequate neuromuscular paralysis.

- Electrode Insertion Complications: If electrodes traverse the pleura, pneumothorax or hemothorax can occur; bleeding at probe sites, pleural effusions, or localized abscess formation have also been reported—mostly grade I–II and rapidly managed.

- Peripheral Nerve Injury: Improper patient positioning under anesthesia can stretch or compress nerves (e.g., brachial plexus), causing temporary sensory or motor deficits that usually resolve within days to weeks.

- Enzyme Elevations: Transient pancreatic enzyme increases and rare short‑lived pancreatitis have been noted; other tissues (breast, brain) show few complications.

Overall, clinical complication rates after IRE compare favorably with other modalities. A systematic review of 16 studies encompassing 129 hepatic tumors reported a 16% overall complication rate, all grade I–II. In pancreatic and prostate trials, most adverse events relate to anesthesia or probe placement, with minimal off‑target tissue injury.

Advantages and Limitations

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Preservation of adjacent vessels and nerves (no collagen matrix damage) | Requires general anesthesia with complete neuromuscular blockade |

| Non‑thermal effect (minimal collateral thermal injury) | Best suited for small to medium tumors (typically < 3–4 cm) |

| Enables the treatment of tumors adjacent to major vessels | Contraindicated in patients with arrhythmias or implanted pacemakers |

| Sharp ablation margins and potential immune stimulation | May require multiple electrodes (increased probe‑site risk) |

| Can be combined with systemic therapies (e.g., chemotherapy) | Limited experience in some organs (e.g., lung, brain); needs further study |

Conclusion

Irreversible electroporation represents an innovative approach for the ablation of solid tumors. It leverages non‑thermal electrical pulses to achieve precise cell death while preserving critical peritumoral structures. Its foremost applications include hepatic, pancreatic, and prostatic tumors, with early clinical data supporting its safety and efficacy. Although long‑term outcome data and standardized treatment protocols are still evolving, IRE holds promise as both a complementary and, in selected cases, alternative modality for managing localized malignancies.