Gene delivery via viral vectors

Gene delivery refers to the introduction of genetic material into cells for various purposes, including gene therapy and other applications. In this approach, effective transfer of the gene into target cells plays a key role. Gene carriers (vectors) are the main component of this method and fall into two primary categories: viral and non‑viral. Viral vectors, due to their high efficiency of gene transfer and their ability to establish stable gene expression in target cells, enjoy great popularity. Clinical studies over the past two decades have shown promising results.

One reason gene delivery with viral vectors is regarded as superior to transfection with naked plasmid DNA is the high efficiency of gene entry into target cells. Viruses have evolved over millions of years, with highly effective mechanisms for penetrating cells and delivering their genetic payload. Therefore, when an engineered virus is used to carry a gene, the process follows a natural pathway and is exceedingly efficient.

The main advantage of this method compared to naked‑DNA transfection is that viral vectors can deliver the gene with higher efficiency to a broader spectrum of cells and, in many cases, sustain gene expression for a longer duration. Moreover, different virus types are tailored for specific applications. For example:

- Adenoviruses are generally used for short‑term, high‑level expression.

- Herpes Simplex Viruses (HSV), due to their natural tropism for neural cells, are highly suitable for long‑term expression in the nervous system.

- Retroviruses and Lentiviruses have the capacity to stably integrate their genes into the host cell genome, making them ideal for applications requiring long-term or permanent expression.

- AAV (Adeno‑Associated Virus): for long‑term expression without genome integration and eliciting minimal immune response.

.

Types of viral vectors

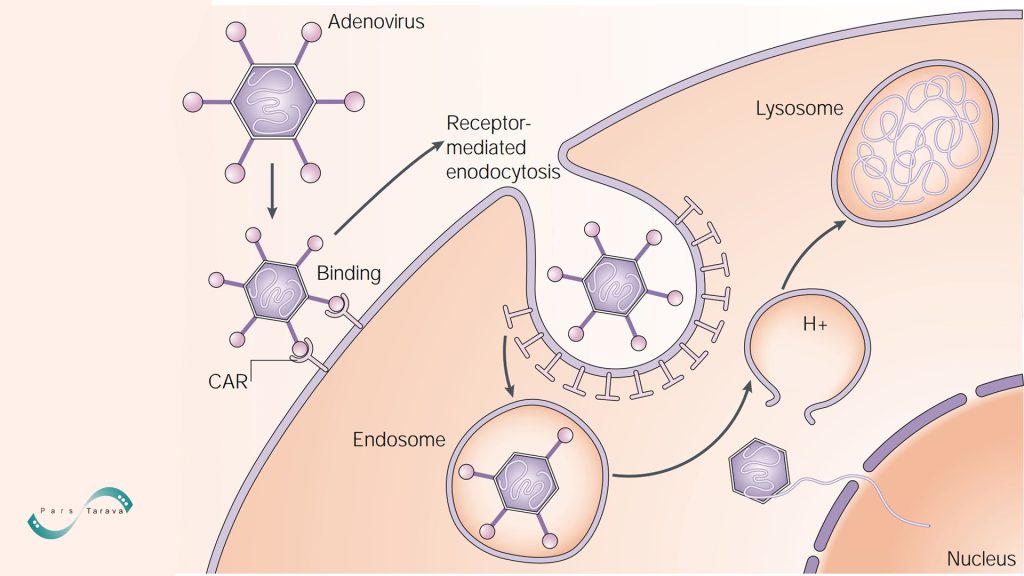

Various viral vectors have evolved to deliver nucleic acids into cells. Enveloped and non‑enveloped viruses employ different strategies to interact with cellular membranes. Enveloped viruses bind specific receptors on the cell surface and then either fuse directly with the plasma membrane or, following receptor‑mediated endocytosis, fuse with the endosomal membrane to release their cargo. Non‑enveloped viruses, by contrast, use virion proteins to penetrate or disrupt the plasma or endosomal membrane. In each case, the viral genome is released into the cytoplasm and transported to its natural site of replication, which may or may not be the nucleus.

.

Types of viral vectors include:

1- Adenoviruses

Adenovirus virions attach to the coxsackie‑adenovirus receptor (CAR) and integrins on the plasma membrane and enter the cell via receptor‑mediated endocytosis. Upon endosomal acidification, the capsid disassembles and is released into the cytosol. Double‑stranded viral DNA then enters the nucleus through nuclear pores. These vectors lack a protein coat beyond the capsid and have a double-stranded genome of approximately 26–45 kb. Adenoviral vectors are popular for gene delivery because they infect both dividing and non-dividing cells with high efficiency, although they can trigger a strong host immune response. Cell-agglutination assays and genomic GC content define six human adenovirus subgroups. A significant advantage is that they can be purified to very high titers—suitable for in vivo use—and can approach nearly 100% gene delivery efficiency if the target cells express the appropriate receptors. In third‑generation “gutless” or HC‑Ad vectors, all viral genes are deleted, leaving only the inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), enabling a cargo capacity of up to ~36 kb.

.

2- Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)

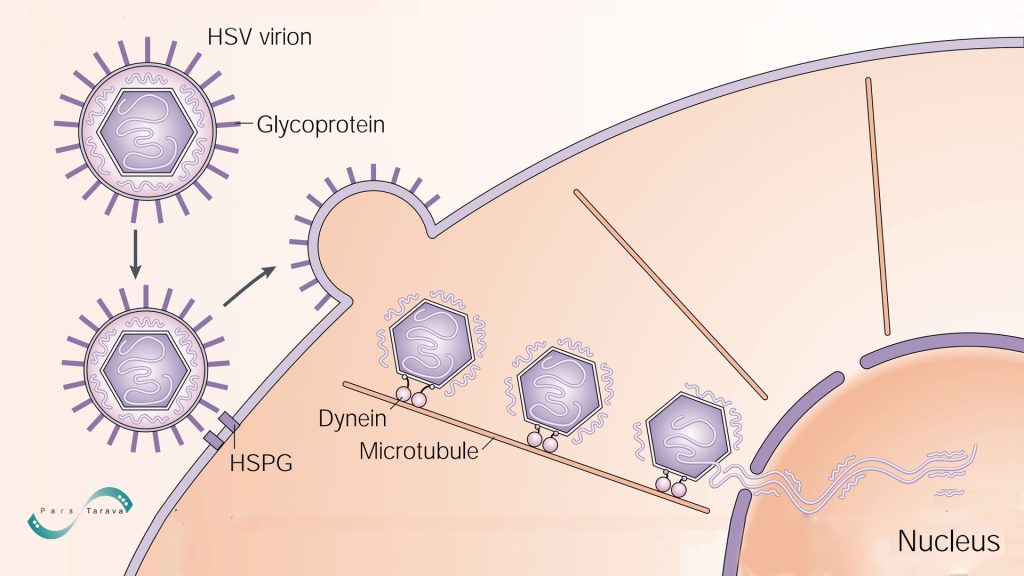

HSV is another viral vector with a huge double-stranded DNA genome (approximately 152 kb). Its virion structure includes an outer lipid envelope studded with numerous glycoproteins and other proteins, surrounding a tegument protein matrix that coats the capsid. These features enable it to carry very large or multiple transgenes simultaneously, granting it a broad host-cell tropism.

The herpesviruses used as vectors include Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 (HSV-1). HSV‑1’s extensive host range and cell‑type tropism have made it a versatile delivery vehicle. Its natural neurotropism makes it especially suitable for targeting neuronal cells in treatments for neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and chronic pain. Recombinant HSV vectors are engineered to lack all disease‑causing genes, serving solely as gene carriers. The main challenges of this vector system are strong immune activation and the complexity of engineering such large genomes.

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) virions attach to the cell surface through interactions between glycoproteins on the virion envelope and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). Additional glycoprotein–receptor interactions mediate subsequent fusion of the envelope with the plasma membrane. The capsid and associated tegument proteins then enter the cytoplasm and are transported via dynein-mediated movement along microtubules to the nucleus, where the double‑stranded viral DNA is released through the nuclear pores.

.

3- Retroviruses

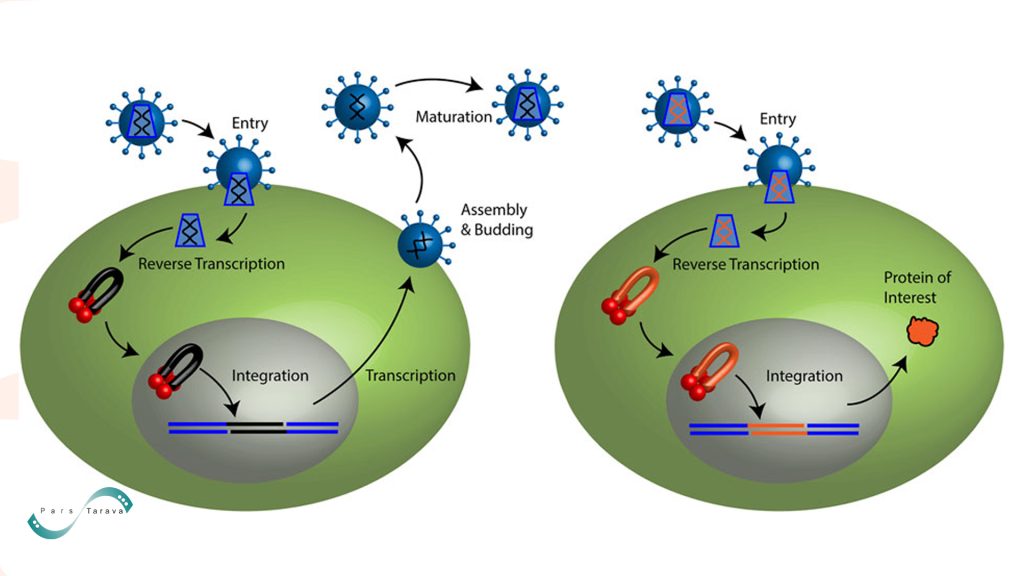

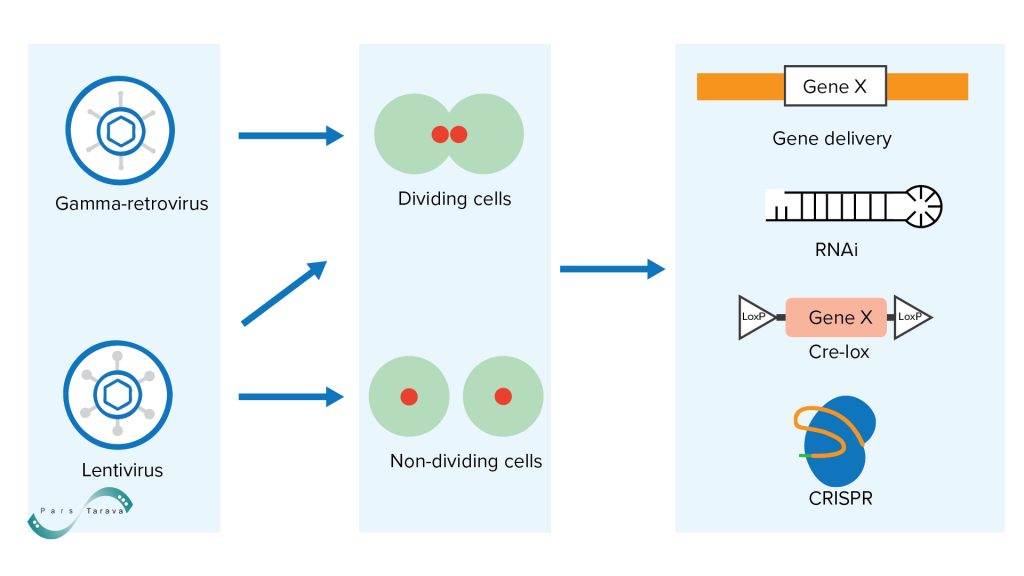

Retroviruses are enveloped, single-stranded RNA viruses approximately 100 nm in diameter. They belong to the Retroviridae family and carry reverse transcriptase within the virion. After entering the target cell, this enzyme converts viral RNA into DNA and integrates the delivered gene into the host genome. Seven retroviral genera are defined by sequence comparisons: simple oncoretroviruses, such as murine leukemia virus (MLV), and more complex lentiviruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and foamy viruses.

The retroviral life cycle and gene delivery by a retroviral vector proceed as follows. Retroviruses can enter the target cell by membrane fusion. The capsid core is then released into the cytoplasm. Reverse transcriptase copies the viral genomic RNA (black lines) into a linear, double‑stranded cDNA. Integrase binds to the ends of this viral cDNA, forming a pre‑integration complex (PIC).

Lentiviral PICs can cross the nuclear membrane, whereas other retroviruses require cell division to access the host genome. Integrase mediates the stable integration of viral DNA (black) into the host genome (blue), resulting in the formation of a provirus. The host transcription machinery then produces viral mRNAs and genomic RNA. Newly formed viral particles assemble and bud from the plasma membrane. Following budding, the viral protease cleaves polyproteins to generate a mature, infectious virion.

Retroviral vector particles recapitulate only the early steps of this cycle. They do not encode viral proteins; only the therapeutic transgene is encoded.

.

4- Lentiviruses

Lentiviral vectors (for example, modified HIV) have the ability to enter the nucleus even in non‑dividing cells and establish long‑term gene expression. For instance, these vectors can maintain a transgene for extended periods in quiescent cells. The replication strategy of retroviruses is unique. After cell entry, the virus is uncoated, and the genomic RNA is transported to the nucleus, where it is reverse‑transcribed by a virion protein into double‑stranded cDNA. A second virion protein, integrase, then inserts this cDNA copy into the host genome.

Lentiviral vectors have a packaging capacity of approximately 8–9 kb, which is somewhat larger than that of AAV vectors. Despite these advantages, the lack of precise control over integration sites in the host genome can pose a risk of insertional mutagenesis. Retroviruses are useful gene-delivery vehicles capable of producing high viral titers (10⁶–10⁸ particles per milliliter) using available packaging cell lines, achieving remarkably stable integration efficiency (nearly 100% in vitro and also very high in vivo), and efficiently generating viral particles. The small viral genome, once converted to cDNA in the lab, is easily manipulated and features a convenient promoter/enhancer system that can drive robust transgene expression.

.

Adeno‑Associated Virus (AAV)

AAV is a small, non‑enveloped, single‑stranded DNA parvovirus that requires a helper virus for replication. AAV vectors provide long‑term, stable transgene expression without integrating into the host genome, forming episomal concatemeric structures in the nucleus. AAV elicits minimal immune responses, making it ideal for chronic therapies. Its drawback is a small packaging capacity (~4–5 kb), which limits the use of larger transgenes.

All these viral vectors have been harnessed to develop successful clinical gene therapies and continue to be refined for safety, specificity, and efficiency.

.

Advantages and Challenges of Gene Delivery via Viral Vectors

Gene delivery via viral vectors offers significant advantages. The most important benefit is the extremely high efficiency of delivering the gene into target cells and establishing long-term expression. These vectors exploit viruses’ natural cell‑entry mechanisms, and through specific genetic engineering, all disease‑causing viral genes are removed. This enables us to leverage the inherent advantages of viral delivery without any risk of viral replication or infection.

On the other hand, significant challenges include activating the host immune system and limited cargo capacity. A strong immune response against viral proteins can reduce therapeutic efficacy and increase the risk of side effects. Additionally, the limited packaging capacity of some vectors (especially AAV) and the potential for random integration of vector DNA into the host genome (notably with retroviruses) are also significant concerns.

.

Other Gene Delivery Methods

Beyond viral vectors, several non-viral methods for gene delivery exist. Chemical approaches, such as lipofection and cationic nanoparticles, can effectively carry DNA or RNA into target cells. Physical methods, such as microinjection (the direct injection of genetic material into the cell nucleus) and the gene gun (shooting DNA-coated particles into tissues), are used in laboratory settings. Advanced technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9, also serve as gene-editing tools that do not require a viral carrier. However, non‑viral methods generally have lower delivery efficiency compared to viral vectors, although they pose fewer safety risks.

.

Electroporation: An Efficient Non‑Viral Alternative

Electroporation is a highly effective non-viral method for gene delivery. In this technique, short, high-voltage electrical pulses create transient pores in the cell membrane, allowing DNA or RNA molecules to pass through. Electroporation is widely used in biological research due to its simplicity and relatively high transfection efficiency. Another advantage is that the genetic material bypasses endosomal degradation and enters the cytoplasm directly, allowing more DNA to reach the nucleus and potentially enhancing overall delivery effectiveness.

Pars Tarava in Iran is the producer of commercial electroporation equipment and the first company in the country to manufacture these devices. For more information, you can contact them at +98 902 405 1862 via phone or WhatsApp.

.

Clinical Applications of Viral Gene Delivery

The use of viral vectors in clinical treatments represents one of the most advanced and promising areas of medical biotechnology. These vectors enable the stable delivery of therapeutic genes into human cells, and in recent years, several successful, regulatory‑approved products have been developed. Below are some of the most notable clinical applications currently in use:

- Luxturna: An AAV2‑based therapy carrying a corrected RPE65 gene to treat Leber congenital amaurosis (inherited blindness).

- CAR‑T Immunotherapy (Kymriah & Yescarta): Cancer treatments that modify patient T cells using lentiviral vectors, approved for various leukemias and lymphomas.

- Zolgensma: An AAV9 vector delivering the SMN1 gene for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in infants.

- Zynteglo: A lentiviral vector carrying the HBB gene for β‑thalassemia, approved by the European Union.

- Strimvelis: A retroviral therapy for ADA‑SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency), approved in Europe.

- Kymriah: The first FDA‑approved CAR‑T therapy, using a lentiviral vector to correct T cells in leukemia patients.

.

Conclusion

Gene delivery via viral vectors is a powerful tool for treating genetic diseases. This approach offers the advantages of high delivery efficiency and long‑term gene expression, but also faces challenges such as host immune responses and vector capacity limits. Therefore, combining viral and non‑viral methods (e.g., electroporation) provides a balanced strategy to enhance both efficacy and safety. As technology advances and interdisciplinary collaborations grow, new therapeutic opportunities in gene therapy are expected to emerge. Viral gene delivery continues to evolve, and each improvement in safety and performance paves the way for innovative treatments.

.

If you are interested in more information, consultation, or acquiring advanced electroporation equipment, the expert team at Pars Tarava is ready to assist you. Contact us by phone or WhatsApp at +98 902 405 1862.

.

Refrences

Viral vector platforms within the gene therapy landscape

Viral Vector-Based Gene Therapy

Recent progress in viral and non-viral therapy.” Recent advances in novel drug carrier systems

Viral vectors for gene delivery to the nervous system

Strategies for Targeting Retroviral Integration for Safer Gene Therapy: Advances and Challenges.

Targeting microglia with lentivirus and AAV: Recent advances and remaining challenges

.